Karelo Finnish epic kalevala protagonists. Kalevala Karelian-Finnish folk epic

Summary "Kalevala" allows you to get acquainted in detail with this famous Karelian-Finnish epic. The book consists of 50 runes (or songs). It is based on epic folk songs. The folklore material was carefully processed in the XIX century by the Finnish linguist Elias Lennort. He was the first to plot separate and isolated epic songs, eliminating certain irregularities. The first edition was published in 1835.

Runes

The brief content of the Kalevala describes in detail the actions in all the runes of this national epic. Generally Kalevala is the epic name of the state in which all the heroes and characters of Karelian legends live and act. This title was given to the poem itself Lennroth.

"Kalevala" consists of 50 songs (or runes). These are epic works written by a scientist in the course of communication with Finnish and Karelian peasants. The ethnographer managed to collect most of the material on the territory of Russia - in the Arkhangelsk and Olonets provinces, as well as in Karelia. In Finland, he worked on the western shores of Lake Ladoga, right up to Ingria.

Translating to Russian language

For the first time, a brief summary of Kalevala was translated into Russian by the poet and literary critic Leonid Belsky. It was published in the journal Pantheon of Literature in 1888.

The following year the poem was printed in a separate edition. For Russian, Finnish, and European scholars and researchers, the Kalevala is a key source of information about the pre-Christian religious views of Karelians and Finns.

To describe the brief content of "Kalevala" you need to start with the fact that in this poem there is no harmonious main plot that could link all the songs together. As it happens, for example, in Homer's epic works, the Odyssey or the Iliad.

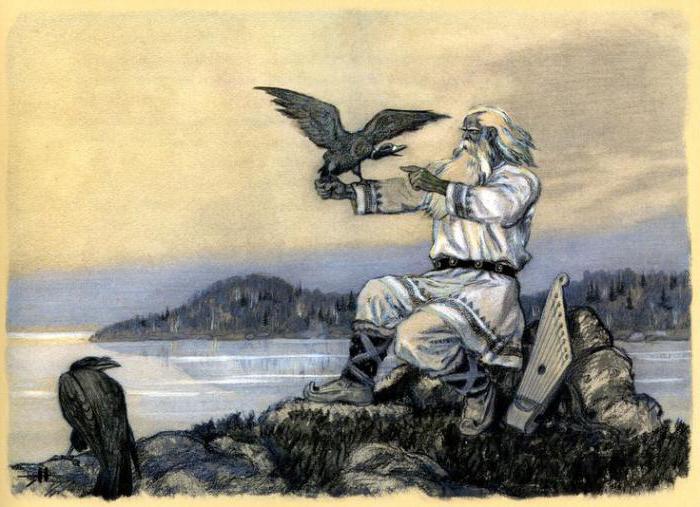

"Kalevala" in a very brief content is an extremely diverse work. The poem begins with the legends and ideas of the Karelians and Finns about how the world was created, how the earth and the sky, all kinds of lights appeared. At the very beginning, the main character of the Karelian epic named Vainamainen is born. It is alleged that he was born thanks to the daughter of air. It is Väinämöinen who arranges the whole earth, starts sowing barley.

Adventures of folk heroes

The epos "Kalevala" in short content tells the story of the travels and adventures of various heroes. First of all - Vainamainen himself.

He meets the beautiful maiden of the North, who agrees to marry him. However, there is one condition. The hero must build a special boat from the fragments of its spindle.

Väinämöinen starts to work, but at the most crucial moment hurts himself with an ax. The bleeding turns out to be so strong that it cannot be eliminated on its own. We have to ask for help from a wise healer. He tells him a folk story about the origin of iron.

The secret of wealth and happiness

The healer helps the hero, relieves him of heavy bleeding. In the epic "Kalevala" in summary, Väinämöinen returns home. In native walls, he reads a special spell that raises a strong wind in the area and transfers the hero to the country of the North to a blacksmith named Ilmarinen.

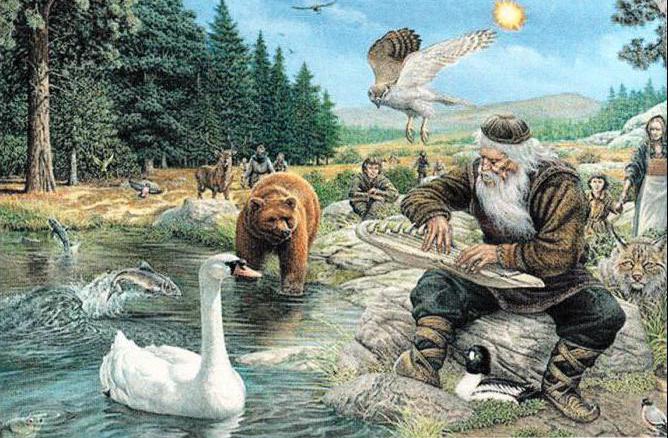

The blacksmith forges at his request a unique and mysterious item. This is the mysterious mill of Sampo, which, according to legend, brings happiness, luck and wealth.

Immediately several runes devoted to the adventures of Lemminkäinen. He is a warlike and powerful sorcerer, a womanly heart conqueror known to the whole district, A cheerful hunter who has only one drawback - the hero is fond of women's charms.

In the Karelian-Finnish epic "Kalevala" (you can read a brief content in this article), its fascinating adventures are described in detail. For example, he somehow finds out about a pretty girl who lives in Saari. And she is known not only for her beauty, but also for her incredibly obstinate character. All fiancés she categorically refuses. The hunter decides by all means to achieve her hands and hearts. The mother is trying in every way to dissuade her son from this thoughtless venture, but to no avail. He does not listen to her and goes on the road.

In Saari, at first, the loving hunter makes fun. But over time, he manages to conquer all the local girls, except for one - impregnable Kyullikki. This is the beauty for which he set off.

Lemminkäinen goes on to take decisive action - kidnaps the girl, intending to take her as his wife to her home. Finally, he threatens all women of Saari - if they tell who actually took Kyllikki, he will start a war, as a result of which all their brothers and husbands will be exterminated.

At first, Kyullikki resists, but as a result agrees to marry a hunter. In return, she takes an oath from him that he will never go to war to her native lands. The hunter promises this, and also takes an oath with his new wife that she will never go to the village to dance, but will be his faithful wife.

Väinamöinen in the netherworld

The plot of the Finnish epic "Kalevala" (a summary is provided in this article) returns to Vainainmeinen. This time is a story about his journey to hell.

Along the way, the hero has to visit the womb of the giant Viipunen. With the latter he is seeking the secret three words that are needed in order to build a wonderful boat. On it, the hero goes to Pohjela. He expects to achieve the location of the northern maiden and marry her. But it turns out that the girl chose him the blacksmith Ilmarinen. They are getting ready to play the wedding.

wedding ceremony

The description of the wedding, the corresponding celebration of the rites, as well as the duties of husband and wife are devoted to several separate songs.

In the Karelian-Finnish epic "Kalevala" in a brief content describes how the more experienced mentor tell the young bride, how she will behave in marriage. The old beggar woman, who comes to the celebration, starts up in the memories of the times when she was young, got married, but she had to divorce, as her husband turned out to be angry and aggressive.

Read at this time of instruction and the groom. He is not told to treat his chosen one badly. He also gives advice to a poor old man who recalls how he instructed his wife.

At the table, the newlyweds are served with all sorts of dishes. Väinämöinen utters a feast song in which he glorifies his native land, all its inhabitants, and separately the owners of the house, matchmakers, bridesmaids and all the guests who came to the festival.

Wedding feast is fun and plentiful. On the way back the newlyweds go to the sleigh. On the way, they break. Then the hero turns to local people for help - it is necessary to go down to Tuonela for the gimlet to fix the sled. This is only a true brave man. Those in the surrounding villages and villages are not located. Then Väinämäinen has to go to Tuonela himself. He repairs the sleigh and safely goes back.

The tragedy of the hero

A tragic episode devoted to the fate of the hero Kullervo is given separately. His father had a younger brother named Untamo, who did not like him and built all sorts of wiles. As a result, a real feud arose between them. Untamo gathered the warriors and killed his brother and his clan. Only one pregnant woman survived, and Untamo took her as a slave. She gave birth to a child, who was named Kullervo. Even in infancy, it became clear that he would grow up a hero. When he grew up, he began to think about revenge.

Untamo was very worried, he decided to get rid of the boy. He was put in a barrel and thrown into the water. But Kullervo survived. He was thrown into a fire, but even there he did not burn. Tried to hang on the oak, but after three days found sitting on a bitch and draw warriors on the bark.

Then Untamo humbled himself and left Kullervo with him as a slave. He nursed the children, ground rye, chopped wood. But he did not succeed. The child was exhausted, rye turned into dust, and in the forest he cut down good logging trees. Then Untamo sold the boy to the blacksmith Ilmarinen.

Blacksmith service

In a new place, Kullervo was made a shepherd. In the work "Kalevala" (the Karelian-Finnish mythological epos, a summary of which is given in this article) describes his service to Ilmarinen.

Once the mistress gave him bread for lunch. When Kullervo began to cut it, the knife crumbled into crumbs, inside was a stone. This knife was the last reminder to the boy about his father. Therefore, he decided to take revenge on his wife Ilmarinen. The angry hero drove the herd into the marsh, where wild animals had eaten the cattle.

He turned bears into cows and wolves into calves. Under the guise of a herd drove them back home. He ordered the hostess to be torn to pieces as soon as she looked at them.

Hiding from the blacksmith's house, Kullervo decided to take revenge on Untamo. On the way, he met an old woman who told him that his father was actually alive. The bogatyr really found his family on the border of Lapland. His parents accepted him with open arms. They considered him long dead. Like her eldest daughter, who went to the forest to pick berries and did not return.

Kullervo remained in the parental home. But even there he could not use his heroic power. All that he undertook was spoiled or useless. Father sent him to pay tribute in the city.

Returning home, Kullervo met a girl, lured her into a sleigh, and seduced her. Later it turned out that this is his missing older sister. Having learned that they are relatives, the young people decided to commit suicide. The girl rushed into the river, and Kullervo reached the house to tell her mother everything. His mother forbade him to say goodbye to life, urging him instead to find a quiet corner and live peacefully there.

Kullervo came to Untamo, destroyed his whole family, destroyed houses. When he returned home, he did not find any of his relatives alive. Over the years, all died, and the house was empty. Then the bogatyr killed himself by throwing himself on a sword.

Sampo Treasures

The final runes of the Kalevala show how Karelian heroes mined Sampo from Pohjola’s treasures. They were pursued by the sorceress-mistress of the North, as a result Sampo was drowned in the sea. Väinämöinen nevertheless collected the fragments of Sampo, with the help of which he rendered many blessings to his country, and also went to fight with various monsters and disasters.

The latest rune tells the legend of the birth of a child virgin Marjatta. This is an analogue of the birth of the Savior. Väinämöinen advises to kill him, because otherwise he will surpass the power of all Karelian heroes.

In response, the baby showered him with reproaches, and the ashamed hero leaves the canoe, giving him his place.

In Kalevala there is no main plot that would link all the runes together. The story begins with a story about the creation of the earth, the sky, the stars and the birth of the air of the Finnish protagonist, Waynemeinen, by the daughter, who arranges the earth and sows barley. It tells about the adventures of a hero who meets a beautiful maiden of the North. Her pure gaze is radiant: High, slim, beautiful, And her face is beautiful: A blush burns on her cheeks, Her entire breast glitters with gold, In her braids silver sparkles. She agrees to become his bride if he creates a boat from the fragments of her spindle. While working, Waynemeinen injured himself with an ax so that the bleeding does not stop. He goes to the healer, who tells the story of the origin of iron. Then, with the help of magic, Waynemeinen arranges the wind and transports the blacksmith Ilmarinen to the country of the North, Pohjola, where he manufactures Sampo for the mistress of the North - an item that gives wealth and happiness. Sampo earned here. Next comes the story of the hero Lemminkainen, the warlike enchanter and the dangerous seducer of women. Then again, Waynemeinen is mentioned: he descends into the underworld, enters the womb of the giant Vipunen and learns from him three words that will help create a boat for the maiden of the North. After that, the hero again goes to Pohjola in order to get the hand of the northern maiden, but she already fell in love with the blacksmith Ilmarinen and married him. In order to win the hand of the beautiful North, the blacksmith overcame three obstacles: I plowed the viper's field, I bridled the Manala of the wolf, I caught a big pike In the black river of the kingdom of Tuoni. The story returns to the adventures of Lemminkainen in Pohjola. Included rune about the hero Kullervo, fell in love by ignorance in his sister. Both, brother and sister, having learned the truth, commit suicide. The next plot is the extraction of the treasure of Sampo from Pohjola by three Finnish heroes. Waynemainen makes cantela (harp), skillfully playing an instrument, he puts to sleep Pohjola’s population. This helps to take away the heroes of Sampo. The mistress of the North is pursuing them for the theft, and he falls into the sea and breaks into fragments. With the help of these fragments, Waynemeinen performs many good deeds for his native country. Sampo fragments planted, Splinters from a motley cover On a toe in the middle of the mist, There on a hazy island, So that they grow and multiply, So that they can transform In rye perfect for bread And in barley for brewing beer. Waynemeinen struggles with various disasters and monsters sent by the mistress of Pohjola to Kalevala. The last rune speaks of the birth of a wonderful child by the virgin Maryatta (the birth of the Savior). He is destined to become more powerful than Waynemeinen, and the latter advises to kill the baby. But the kid is ashamed of the hero by such a non-heroic murder, and Waynemeinen sails forever from Finland, giving way to the baby Marjatta, the recognized ruler of Karelia.02.02.2012 35470 2462

Lesson 9 “KALEVALA” - KARELO-FINNSKY MYTHOLOGICAL EPOS

Goals: to give an idea of the Karelian-Finnish epic; to show how the ideas of the northern peoples about the world order, about good and evil, are reflected in the ancient runes; to reveal the depth of ideas and the beauty of the images of the ancient epic.

Methodical techniques: text reading, analytic conversation, revealing reading comprehension.

During the classes

I. Organizational moment.

Ii. Post topics and lesson objectives.

Iii. Study a new topic.

1. The word of the teacher.

Today we will get acquainted with the Karelian-Finnish epic “Kalevala”, which occupies a special place among the world's epics - the content of the poem is so peculiar. It narrates not so much about military campaigns and feats of arms, but about the initial mythological events: the origin of the universe and the cosmos, the sun and stars, the earth's firmament and the waters, of all things on earth. In the myths of Kalevala everything happens for the first time: the first boat is built, the first musical instrument and the music itself is born. The epos is full of stories about the birth of things, it has a lot of magic, fantasy and miraculous transformations.

2. Work in a notebook.

Folk epic - a poetic variety of narrative works in prose and verse; as an oral work, the epic is inseparable from the performing art of the singer, whose mastery is based on following national traditions. People's epic reflects the life, lifestyle, beliefs, culture, self-consciousness of people.

3. Conversation on issues.

- “Kalevala” is a mythological folk epic. What are myths and why did people create them? (Myths are stories created by popular fantasy, in which people explained various phenomena of life. The myths set out the most ancient ideas about the world, its structure, the origin of people, gods, and heroes.)

“What myths are you familiar with?” (With the myths of ancient Greece.)Remember the most vivid heroes of myths. (The strong and courageous Hercules, the most skillful singer Arion, the brave and cunning Odyssey.)

4. Work with the textbook article (p. 36–41).

Reading aloud articlesabout the epic “Kalevala” by several students.

5. Analytical conversation.

The conversation is based on questions 1–9 presented on p. 41 textbooks.

- Where and when, according to scientists, was the Karelian-Finnish epic formed? Who literally processed and recorded it?

- How many runes (songs) does the composition Kalevala consist of?

- What are the ancient runes talking about?

- What heroes "inhabit" the epos "Kalevala" and what natural elements accompany their deeds?

- What are the northern and southern points of this beautiful country called?

- Who ordered whom and why to make the wonderful mill Sampo and what does this mill symbolize?

- How did the blacksmith Ilmarinen work on the creation of Sampo?

- What happened to Sampo afterwards?

- Tell us about the traditions, working days and holidays, about the heroes of Kalevala. Compare with the heroes of epics. What do they have in common and what is different?

Iv. Summing up the lesson.

Word of the teacher.

The epos "Kalevala" is an invaluable source of information about the life and beliefs of ancient northern peoples. Interestingly, the images of Kalevala took an honorable place even on the modern coat of arms of the Republic of Karelia: the eight-pointed star crowning the coat of arms is the symbol of Sampo - the guiding star of the people, the source of life and prosperity, “the happiness of the eternal beginning.”

The whole culture of modern Karelians is permeated with the echoes of Kalevala. Annually, within the framework of the Kalevala Mosaic, an international cultural marathon, folk festivals and festivals are held, including theatrical performances based on Kalevala, performances by folklore groups, dance festivals, exhibitions of Karelian artists continuing the traditions of the ethnic culture of the Finno-Ugric peoples of the region.

Homework: pick 2-3 proverbs on various topics, explain their meaning.

Individual task: retelling-dialogue (2 students) of Anikin's article “The Wisdom of Nations” (p. 44–45 in the textbook).

Download material

The full text of the material, see the downloadable file.

The page shows only a fragment of the material.

The name “Kalevala”, given to the poem by Lonnrot, is the epic name of the country in which Karelian folk heroes live and operate. Suffix la means residence, so Kalevala - this is the place of residence of Kalev, the mythological ancestor of the bogatyrs Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, Lemminkäinen, sometimes called his sons.

The material for the addition of an extensive poem of 50 songs (runes) was Lönnrot individual folk songs, part of the epic, part of the lyric, part of the magical character, recorded from the words of Karelian and Finnish peasants by Lönnrot himself and his predecessors. The best remembered were ancient runes (songs) in Russian Karelia, in Arkhangelskaya (Vuokkiniemi parish - Voknavolok) and Olonets gubernias - in Repola (Reboly) and Khimole (Gimola), as well as in some places in Finland Karelia and on the western shores of Lake Ladoga, before Ingria.

In Kalevala there is no main plot that would link all the songs together (as, for example, in the Iliad or the Odyssey). Its content is extremely diverse. It opens with a story about the creation of the earth, the sky, the stars and the birth of the air of the protagonist of the Karelians, Väinämöinen, by the daughter, who arranges the earth and sows barley. The following describes the different adventures of the hero, who meets, by the way, the beautiful maiden of the North: she agrees to become his bride if he miraculously creates a boat from the fragments of her spindle. Having begun work, the hero wounds himself with an ax, cannot calm down the bleeding and goes to the old medicine man, to whom the legend tells about the origin of iron. Returning home, Väinämöinen raises the wind with incantations and transports the blacksmith Ilmarinen to the country of the North, Pohjol, where he, according to the promise given to Väinämöinen, forges the mysterious object that gives wealth and happiness for the mistress of the North - the Sampo mill (runes I-XI))

The following runes (XI-XV) contain an episode about the adventures of the hero Lemminkäinen, the warrior magician and the seducer of women. Further, the story returns to Väinämöinen; describes his descent into hell, his stay in the womb of the giant Viipunen, his extraction of the last three words needed to create a wonderful boat, the departure of the hero in Pohlёlu in order to get the hand of the northern maiden; however, the latter preferred the blacksmith Ilmarinen to him, whom he marries, and the wedding is described in detail and wedding songs that set forth the duties of the wife and husband (XVI-XXV) are given.

The Runes (XXVI-XXXI) again tell of Lemminkäinen’s adventures in Pohjøl. The episode about the sad fate of the hero Kullervo, who seduced his sister by ignorance, as a result of which both brother and sister commit suicide (runes XXXI-XXXVI), belongs to the best parts of the entire poem in the depth of feeling that sometimes reaches true pathos. The runes about the hero Kullervo were recorded by Lönnrot’s assistant, folklorist Daniel Europeus.

Further runes contain a lengthy story about a common enterprise of three Karelian heroes - about how the treasures of Sampo from Pohjola (Finland) were mined, how Väinämöinen made kantele and played on it fascinated the whole nature and put to sleep the population of Pohjoly, as Sampo was taken away by heroes. It tells about the pursuit of heroes by the Northern mistress, the fall of Sampo into the sea, the blessings rendered by Väinämönen to his native country through Sampo fragments, his struggle with various disasters and monsters sent by the mistress of Pohjola to Kalevala, about the marvelous play of the hero to the Kalevala, them when the first one fell into the sea, and about the return of the sun and the moon, hidden by the mistress of Pohjola (XXXVI-XLIX).

The last rune contains the folk-apocryphal legend of the birth of a wonderful child by the virgin Maryatta (the birth of the Savior). Väinämöinen gives him advice to kill him, as he is destined to surpass the power of the Karelian hero, but a two-week-old baby shoots Väinämöinen with reproaches of injustice, and the ashamed hero sings a wonderful song for the last time, leaving the martyr, giving place to the infant, to the rest of the world, giving place to the baby, to the child, to the rest of the world.

Philological and ethnographic analysis

It is difficult to specify a common thread that would link the various episodes of the Kalevala into one artistic whole. E. Aspelin believed that the main idea of her - the glorification of the change of summer and winter in the North. Lönnrot himself, denying the unity and organic connection in the runes of Kalevala, admitted, however, that the songs of the epic are directed towards proving and figuring out how the heroes of the Kalev country subordinate the population of Pohyola. Julius Kron argues that Kalevala is imbued with one idea - to create Sampo and get it into the ownership of the Karelian people - but he acknowledges that the unity of the plan and the ideas are not always seen with the same clarity. The German scientist von Pettau divides the Kalevala into 12 cycles, completely independent of each other. The Italian scientist Comparetti, in his extensive work on Kalevala, concludes that it is not possible to assume unity in the runes, that the combination of runes made by Lönnrot is often arbitrary and still gives the runes only a ghostly unity; Finally, it is possible to make other combinations from the same materials according to some other plan.

Lönnrot did not discover the poem, which was hidden in the runes (as Steinthal believed) - it did not open because the people did not exist such a poem. The runes in the oral transmission, even if they were contacted by the singers in several ways (for example, several adventures of Väinämöinen or Lemminkäinen), represent the whole epic as little as the Russian epics or Serbian youth songs. Lönnrot himself admitted that when he joined the runes into an epic, some arbitrariness was inevitable. Indeed, as the test of Lonnrot's work showed him with the versions written by him and other rune collectors, Lönnrot chose such retellings that best fit the plan he had drawn, rallying the runes from particles of other runes, made additions, and made the verses Fleece (50) can even be called his work, although based on folk legends. For his poem, he skillfully disposed of all the wealth of Karelian songs, introducing, along with narrative runes, songs of ritual, conspiracy, family, and this gave Kalevala considerable interest as a means of studying worldview, concepts, everyday life and poetic creativity of the Finnish common people.

Characteristic of the Karelian epos is the complete absence of a historical basis: the adventures of the heroes are distinguished by their purely fabulous character; no echoes of the historical clashes of the Karelians with other nations were preserved in the runes. In Kalevala there is no state, people, society: she knows only the family, and her heroes accomplish feats not for the sake of their people, but for the achievement of personal goals, like heroes of wonderful fairy tales. Types of warriors are in connection with the ancient pagan views of the Karelians: they accomplish feats not so much with the help of physical strength, as through conspiracies, like shamans. They can take a different look, wrap other people in animals, miraculously transported from place to place, cause atmospheric phenomena - frosts, fogs, and so on. There is also the proximity of the heroes to the deities of the pagan period. It should be noted also the high importance attached by the Karelians, and later by the Finns, to the words of the song and music. Prophetic man who knows the runes, conspiracies, can work wonders, and the sounds extracted by the wondrous musician Väinämönen from kantele, conquer the whole of nature.

In addition to the ethnographic, Kalevala is also of high artistic interest. Its advantages include: simplicity and brightness of images, a deep and vivid sense of nature, high lyrical outbursts, especially in the image of human grief (for example, mother's longing for a son, children for parents), healthy humor that permeates certain episodes, a successful characterization of the characters. If you look at Kalevala as an integral epic (Crohn’s view), then it will have many flaws, which, however, are characteristic of more or less all oral folk epic works: contradictions, repetitions of the same facts, too large dimensions of some particulars in relation to the whole. The details of some forthcoming action are often spelled out in great detail, and the action itself is told in a few minor verses. This kind of disproportion depends on the memory properties of one or another singer and is often found, for example, in Russian epics.

However, there are historical facts, in an interlacing with geography, partially confirming the events described in the epic. To the north of the present village of Kalevala, there is Lake Topozero - the sea through which the heroes sailed. On the shores of the lake settled saami - the people of Pohjola. Saami had strong sorcerers (Old Louhi). But the Karelians were able to push the Sami far to the north, subdue the population of Pohjola and conquer the latter.

Kalevala Day

Every year on February 28, the Day of the National Epos of Kalevala is celebrated - the official day of Finnish and Karelian culture, the same day is dedicated to the Finnish flag. Every year in Karelia and Finland the “Kalevalsky Carnival” takes place, in the form of a street costume procession, as well as theatrical performances based on the epic plot.

Kalevala in art

|

Please provide information in an encyclopedic form and scatter it into relevant sections of the article. According to the decision of the Wikipedia Arbitration Committee, it is preferable to base lists on secondary generalizing ones that contain criteria for the inclusion of elements in the list. |

- The first written mention of the heroes of Kalevala is contained in the books of the Finnish bishop and first printer Mikael Agricola in the 16th century.

- The first monument to the hero of Kalevala was erected in Vyborg in 1831.

- The poem was first translated into Russian in 1888 by the poet and translator Leonid Petrovich Belsky.

- In Russian literature, the image of Väinnemüinen is found for the first time in the poem of Decembrist FN Glinka “Karelia”

- The first painting on the plot of "Kalevala" was created in 1851 by the Swedish artist Johan Blakstadius.

- The first work on the plot of Kalevala was the play by the Finnish writer Alexis Kivi, Kullervo (1860).

- The most significant contribution to the musical incarnation of Kalevala was made by the classic of Finnish music, Jan Sibelius.

- Kalevala has been translated into Ukrainian by linguist Yevgeny Timchenko. In Belarus, the first translation was made by the poet and writer Mikhas Mashara. Newest - translator Yakub Lapatka.

- Latvian translation by Linard Lyzen.

- Nenets translation was made by Vasily Ledkov.

- The plots of Kalevala are present in the work of many artists. In the Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Karelia a unique collection of works of fine art on the themes of the Kalevala epos is collected. The cycle of paintings with scenes from the Kalevala by the Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela is widely known.

- In 1933, the Academia publishing house produced Kalevala with illustrations and in the general decoration of the students of Pavel Filonov, Masters of Analytical Art T. Glebova, A. Poret, M. Tsybasov, and others. Filonov himself was an editor of illustrations and design.

- Based on Kalevala, the Karelian composer Helmer Sinisalo wrote the ballet Sampo, which was first staged in Petrozavodsk on March 27, 1959. This work was repeatedly performed both in the USSR and abroad.

- In 1959, a joint Soviet-Finnish film Sampo (directed by Alexander Ptushko, screenplay by Väinö Kaukonen, Viktor Vitkovich, Grigory Yagdfeld) was made based on Kalevala.

- In 1982, Finnish director Kalle Holmberg filmed a 4-part film adaptation of Kalevala for television - “The Iron Age. Tales of Kalevala, awarded the prizes of the Finnish and Italian Film Academy. In 2009, the film was released in Russia with a set of two DVDs.

- John Tolkien's The Silmarillion was created under the impression of Kalevala.

- Influenced by the Kalevala, Henry Longfellow created the “Song of Haiwatat”. Under the impression of the English translation of the Finnish epic by William Kirby, Tolkien’s first prose work, “The Life of Kulervo,” was created.

Among the first propagandists of Kalevala were Jacob the Grotto in Russia, Jacob Grimm in Germany.

Maxim Gorky put the Kalevala on a par with Homer's epic. In 1908, he wrote: “Individual creativity did not create anything equal to the Iliad or the Kalevala.” In 1932, he calls the Finno-Karelian epos "monument of verbal creativity." “Kalevala” is mentioned in the second volume of “The Life of Klim Samgin”, in chapters on the hero’s Finnish impressions: “Samghin recalled that as a child he read Kalevala, a gift from his mother; This book, written with poems that jumped past memory, seemed boring to him, but the mother still forced her to read it to the end. And now, through the chaos of everything he experienced, the epic figures of the heroes of Suomi, the fighters against Hiysi and Loukhi, the elemental forces of nature, her Orpheus Väinnemöinen ... jolly Lemminkäinen-Baldur Finov, Ilmarinen, who skalved Sampo, the treasure of the country, emerged. ” The motives of Kalevala are Valery Bryusov, Veelimir Khlebnikov, Sergey Gorodetsky, Nikolai Aeev. "Kalevala22 was in the library of Aleksandr Blok.

Kalevala was highly appreciated by the national poet of Belarus Yakub Kolas about his work on the poem “Symon the Musician”, he said: “Kalevala” gave me a good impetus to work ... And its numerous creators and I drank from one source, only Finns on the seashore among the rocks, and we are in our forests and marshes. No one owns this living water, it is open to many and for many. And in some ways the joy and grief of every nation is very similar. So the works may be similar ... I was ready to bow at Lonnrot's feet. "(According to the book by Maxim Luzhanin" Kolas tells about himself ")

V. G. Belinsky could not assess the world significance of the Kalevala. The great critic was familiar with the Finnish epic only in a bad, prosaic retelling. His tense relationship with Ya. K. Groth, the main then popularizer of Finnish literature in Russia, rejection of the Slavophile idealization of folk archaic (Finland of that time, like the Slavic countries, was cited by Slavophiles, for example, Shevyrev, as an example of patriarchal imperfection in opposition to “depraved” Europe ). In a review of the book by M. Eman, “The main features of the ancient Finnish epic of Kalevala”, Belinsky wrote: “We are the first to be ready to give justice to the beautiful and noble feat of the city of Lönnrot, but we do not consider it necessary to go into exaggeration. How! all the European literature, except Finnish, turned into some ugly market? ... ”. “Furious Vissarion” objected to comparing “Kalevala” with the ancient epos, pointed to the underdevelopment of contemporary Finnish culture: “A different national spirit is so small that it will fit in a nutshell, and another is so deep and wide that it lacks the whole earth. Such was the national spirit of the ancient Greeks. Homer is far from exhausted it all in his two poems. And who wants to get acquainted and get accustomed to the national spirit of ancient Hellas, Homer alone is not enough, but for this purpose both Hesiod, tragedians, Pindar, comedian Aristophanes, philosophers, historians, and scientists will be necessary, and there still remains architecture and sculpture and finally the study of domestic home and political life. " (Belinsky V. G. Complete Works of Vol. X, 1956 p. 277-78, 274 M.)

- In 2001, the children's writer Igor Vostryakov retold the Kalevala for children in prose, and in 2011 made a retelling of the Kalevala in verse.

- In 2006, the Finnish-Chinese fantasy film “Warrior of the North” was filmed, the plot of which is based on the interweaving of Chinese folk legends and the Karelian-Finnish epic.

Use name

- In the Republic of Karelia there is the Kalevala National District and the settlement of Kalevala.

- In Petrozavodsk and Kostomuksha there is Kalevala street.

- The Kalevala is a corvette in the Baltic fleet of the Russian Empire in 1858–1872.

- Kalevala is a bay in the southern part of Posiet Bay in the Sea of Japan. Surveyed in 1863 by the crew of the Kalevala corvette, named after the ship.

- There is a Kalevala cinema and a Kalevala bookstore chain in Petrozavodsk.

- In Syktyvkar, there is the Kalevala covered market.

- Kalevala is a Russian folk-metal band from Moscow.

- “Kalevala” is a song by Russian rock bands Mara and Khimera.

- In the Prionezhsky district of the Republic of Karelia, the Kalevala hotel has been operating in the village of Kosalma since the 1970s.

- In Finland, since 1935, under the brand Kalevala koru jewelry made in the traditional technique with the national Baltic-Finnish ornament.

- In Petrozavodsk, in the park named after Elias Lonnrot, a fountain was installed in memory of the heroes of the Kalevala epic.

Translations

Russian translations and adaptations

- 1840 - Small passages in the Russian translation are given by Ya. K. Groth (Sovremennik, 1840).

- 1880-1885 - Several runes in Russian translation published by G. Helgren ("Kullervo" - M., 1880; "Aino" - Helsingfors, 1880; runes 1-3 Helsingfors, 1885).

- 1888 - Kalevala: Finnish folk epic / Complete poetic translation, with a preface and notes by L. P. Belsky. - SPb .: N.A. Lebedev Printing House, Nevsky Prospect, 8., 1888. 616 p.). It was reprinted many times in the Russian Empire and the USSR.

- 1960 - From the poem “Kalevala” (“The Birth of Kantele”, “Golden Maiden”, “Aino”) // S. Marshak: Op. in 4 t., t. 4, p. 753-788.

- 1981 - Lyubarskaya A. Retelling for children of the Karelian-Finnish epos “Kalevala”. Petrozavodsk: Karelia, 1981. - 191 p. (poetic excerpts from the translation of L. P. Belsky).

- 1998 - Lönnrot E. Kalevala. Translated by Eino Kiuru and Armas Mishin. Petrozavodsk: Karelia, 1998. (Reprinted by Vita Nova publishing house in 2010).

- 2015 - Pavel Krusanov. Kalevala Prose retelling. St. Petersburg, K.Tublins Publishing House. ISBN 978-5-8370-0713-2

- German translations of Kalevala: Schiffner (Helsingfors, 1852) and Paul (Helsingfors, 1884-1886).

- French translation: Leouzon Le Duc (1867).

- Swedish translations: Kastrena (1841), Collan (1864-1868), Herzberg (1884)

- English translation: I. M. Crawford (New York, 1889).

- Translation in eighteen runes: H. Rosenfeld, “Kalevala, the folk epos of the Finns” (New York, 1954).

- Translation into Hebrew (in prose): trans. Sarah tobiah, “Kalevala, the land of heroes” (Kalevala, Eretz ha-giborim), Tel Aviv, 1964 (later reprinted several times).

- Translation into Belarusian: Jakub Lapatka Kalevala, Minsk, 2015, Poraklady on ўsimple peraklad on Belarusian MOV

Plan

Introduction

Chapter 1. Historiography

Chapter 2. The history of the creation of "Kalevala"

1. Historical conditions for the emergence of "Kalevala" and problems of authorship

2.2. Circumstances of the creation of "Kalevala" as a historical source

Chapter 3. Daily Life and Religious Views of the Karelian-Finns

1 Main epic stories

2 Heroic Images of the Kalevala

3 Daily life in the Kalevala runes

4 Religious Representations

Conclusion

List of sources and literature

Introduction

Relevance.Epic work is universal in its functions. Fabulous fiction is not separated in it from the real. The epos contains information about gods and other supernatural beings, fascinating stories and instructive examples, aphorisms of worldly wisdom and examples of heroic behavior; its instructive function is as integral as its cognitive one.

The publication one hundred and sixty years ago of the Kalevala epic became epochal for the culture of Finland and Karelia. On the basis of the epos many rules of the Finnish language were fixed. A new presentation appeared on the history of this region in the 1st millennium BC. The images and scenes of the epic had a great influence on the development of Finnish national culture, in its most diverse areas - literature and literary language, drama and theater, music and painting, even architecture. . Thus, Kalevala influenced the formation of the Finns national identity.

Interest in this epic is not waning in our days. Almost every writer, artist, composer of the Finnish republic, regardless of his nationality, has experienced the Kalevala influence in one form or another. National festivals, contests, seminars and conferences are held annually. Their main goal is to preserve the traditions of rune chants, to spread the national musical instrument Kantale, to continue the study of runes.

But the meaning of the Kalevala is also important in the context of global culture. To date, Kalevala has been translated into more than 50 languages, about one hundred and fifty prose narrations, abridged editions and fragmentary variations are also known. Only in the 1990s. published more than ten translations into the languages of the peoples: Arabic, Vietnamese, Catalan, Persian, Slovene, Tamil, Hindi, and others. Under its influence, the Estonian epos "Kalevipoeg" by F. Kreuzwald (1857-1861), the Latvian epic "Lachplesis" by A. Pumpur (1888) were created; The American poet Henry Longfellow wrote on his Indian folklore song "Song of Haiwatt" (1855).

Scientific novelty. "Kalevala ”has repeatedly been the object of research of domestic and foreign specialists. The artistic originality and unique features of the epos, the history of its origin and development are revealed. However, despite some achievements in studying Kalevala, its influence on the development of national culture of different countries and peoples, reflection of images and plots of the great epos in the works of individual writers and poets, artists and composers, world cinema and theater has been little studied. In fact, the Kalevala has not been studied comprehensively as a source on the ancient history of the Finns and Karelians.

The object of our study - The history of the peoples of Northern Europe in antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Subject of study - Karelian-Finnish epic "Kalevala".

Purpose of the study:

On the basis of a comprehensive analysis to prove that the great epic of the Karelian-Finnish people "Kalevala" is the source for the ancient and medieval history of Finland.

The implementation of the research goal involves the following tasks:

.Study the problem historiography and determine its priorities

.Identify the historical conditions of the Karelian-Finnish epos and its authorship.

.Identify the circumstances that influenced the creation of the Kalevala and its structure

.Based on the analysis of the content of Kalevala, reconstruct the daily life of the ancient Karelian-Finns.

.To determine the meaning of the “Kalevala” to characterize the religious ideas of the Karelian-Finnish people.

Chronological scope of the study.After a thorough analysis of the epos, features were identified that allow the approximate chronology of the Kalevala to be defined - from the 1st millennium BC to the 1st millennium AD. In some specific cases, it is possible to go beyond this, which is determined by the purpose and objectives of the work.

Geographic scope. - The territory of modern Finland and the Scandinavian Peninsula, as well as the north-western regions of Russia and the Eastern Baltic.

Research Method: historical analysis

The purpose and objectives of the graduation essay determined its structure. This work is from the introduction, three chapters and conclusion.

Along with Kalevala, which is the natural basis of our research, we rely in our work on a number of other sources and documents on the history of the Karelian-Finnish people, as well as on the achievement of national and foreign historiography.

Chapter I. Historiography

Source study base of this study is represented by various groups of sources. From the group of folklore sources, the first to be called the epos “Kalevala”. It was written and published by E. Lennrot in its final version in 1849. This work consists of 50 runes or twenty-two thousand poems and is put on its importance by researchers with such world-famous epics as Odyssey, Mahabharata or Song about the Nibelungs.

Based on the region of the study, we considered such a source as the “Elder Edda”. It is a collection of songs about gods and heroes, recorded in the middle of the XIII century. And it contains ten mythological and nineteen heroic songs, which are interspersed with small prose inserts explaining and supplementing their text. The songs of “Edda” are anonymous, from other monuments of epic literature they are distinguished by the laconism of expressive means and the concentration of action around a single episode of the tale. Of particular interest is the "Revelation of Velva", which contain the idea of the universe, and "High Speech", which are instructions in the wisdom of life. In addition, we used the “Younger Edda”, written by Snorri Sturluson around 1222-1225, and consisting of four parts: “Prologue”, “Gulvi's Visions”, “Poetry Language” and “List of sizes”.

Sources of personal origin are presented in this study by such a work as “The Journey of Elias Lönnrot: Travel Notes, Diaries, Letters. 1828-1842. On the basis of this source, important conclusions were made concerning the problem of authorship of Kalevala, the interpretation of the plan and the mechanism for selecting material for creating an epos. This travel diary is also indispensable for ethnographic research, as it contains information regarding the wedding ritual of the Karelians of the mid-19th century.

In the collections of documents on the history of Karelia in the Middle Ages and Modern Times, such documents as the preface of M. Agrikola to the Psalms of David, The Story of Karel Nousia, The Letter of the Novgorod Bishop Theodosius helped to confirm a number of data relating to the life and religion of the ancient Finns and Karelia .

Archaeological data are also of great importance. Since no written sources of this period have been found, only they can prove or disprove the information given in the epic. This was especially true of the issue of dating the transition to active use in iron metallurgy. It should be noted also the great connection in the work between archaeologists and the Kalevala, their constant interaction. We can judge this by permanent links in various archaeological research on this epic.

The historiography of this topic is quite extensive. It is necessary to consider and analyze the opinions of various scientists involved in the epic of Kaleval since its publication on the degree of its historicity. What directly relates to the stated research topic.

Finnish scientist MA Castren was one of the first to start developing this problem. He held a peculiar look at the historicity of the Karelian-Finnish epic. Proceeding from the fact that in primitive times it was impossible to create such broad epic works as “Kalevala”, Castren “believed that it was difficult to trace in the Finnish epic whatever the general idea that would link different episodes of“ Kalevala ”into one artistic whole. " Different runes on the themes of the Kalevala, in his opinion, appeared at different times. And the residence of the heroes of the epos - “Kalevala” he represented as a kind of historical point, something like a village. The relationship between Kalevala and Pohjola Kastren viewed as a historical reflection of the relationship between the Karelian and Finnish clans. At the same time, he believes that historical figures cannot be types of heroes.

After the first edition of Kalevala in 1835, many Russian and Western European authors joined the study of the Karelian-Finnish epos and its historical basis. In the Russian Empire, the Decembrists were the first to notice the Kalevala. Fyodor Glinka became interested in the plot of the Karelian rune about the game of Väinämöinen on Kantala and made a translation of this rune into Russian. Some attention was paid to the Karelian-Finnish epos by critic V.G. Belinsky. So he wrote a review of the book by Eman, “The main features of the ancient epic of Kalevala”. The same Russian scientists as Afanasyev, Schiffner tried to compare the subjects of the Karelian-Finnish epic with the Greek and Scandinavian, for example, the production of Kantale Väinämöinen and the creation of Hermes Kifara; Lemminkäinen's death episode and Balder's demise.

In the second half of the century, the theory of borrowing replaces mythological interpretations. Representatives of such views are P. Field, Stasov, A.N. Veselovsky. All of them deny the historicity of the runes and see in them only mythology.

At the end of the 19th century, it became interesting among Russian scientists to get directly acquainted with the sources used by Lönnrot in the Kalevala. In this regard, the ethnographer V.N. Maykov notes that Lonnrot himself “denied any unity and organic connection in the songs of Kalevala. And at the same time he adhered to another point of view, according to which “the Finnish folk epic is a whole, but it is imbued from beginning to end with one idea, namely the idea of creating Sampo and getting it for the Finnish people.”

But there were other views, in particular V.S. Miller and his student Shambinago tried to trace the relationship of the Karelian-Finnish epic and the works of Russian folk art. They discussed the issue of the historical conditions of the convergence of the Russian epic hero Sadko with the image of the hero of the Kalevala runes Väinämöinen. So vs Miller wrote about this: “Finnish legends about the sacred lake Ilmen, of course, had to become known to the Slav population, go to him ... and merge with his family traditions.” Such views had a serious impact on the development of the views of Finnish folklorists of the first half of the twentieth century.

The application of the Indo-European theory to the study of the Karelian-Finnish epic led J. Grima to a comparison of the Kalevala with the Hindu epic. He saw in the epic a reflection of the ancient struggle of the Finns with Lapps. Another philologist, M. Muller, was looking for comparative material for the Kalevala runes in Greek mythology. He saw the main advantage of Kalevala in that it opened a treasury of previously unseen myths and legends. Therefore, he puts it on a par with such great epos of the myth as “Mahabharata”, “Shahname”, “Nibelungs” and “Iliad”. The Finnish philologists were also influenced by some of the research of the German philologist von Tettats, who considered the runes about the manufacture of Sampo and his abduction as the main content of Kalevala.

Of the French philologists, we can mention L. de Duke, one of the first translators of Kalevala. He, like Lönnrot, developed the concept of the historical origin of the Karelian-Finnish epic. As for the English and American philologists, they intensively developed the theme of the influence of Kalevala on the poem of the American poet Longfellow “Song of Haiwatt”.

Some tried to trace the reflection of the magical worldview in the Karelian-Finnish runes and compare the Finnish runes with the ancient Anglo-Saxon myths. The Italian philologist D. Comparetti paid considerable attention to Kalevala, publishing a monograph on the national poetry of the Finns and Karelians at the end of the 19th century. “In all Finnish poetry,” wrote Comparetti, “the militant element finds rare and weak expression. Magic songs, with the help of which the hero defeats his opponents; they are not, of course, chivalrous. ” Therefore, Comparetti denied in the runes the existence of direct borrowing. In the Karelian-Finnish runes, he saw such a clear manifestation of nation-wide poetry that he refused to prove the fact of their borrowing by the Finns from Norwegian poetry, Russian epics, and other Slavic songs. But at the same time, Comparetti was inclined to deny the negation of the historical reality in the runes, since he did not see in this epic even the most basic ethnic and geographical ideas.

And in the twentieth century, Russian scientists continued to actively study the Kalevala, the main problem was its origin (popular or artificial). In 1903, an article by V.A. Gordlevskogo dedicated to the memory of E. Lonnrot. In his arguments about what Kalevala is, he relied on the research of A.R. Niemi (“Composition of“ Kalevala ”, Collection of songs about Väinämöinen”). In this article, the Russian scientist argues with the carriers of the Western theory of the origin of Karelian epic runes (J. Kron), who exaggerated the Baltic-German influence through the Vikings and Varangians on the Karelian and Finnish epic. For V. Gordlevsky, the Kalevala is the “undivided property of the entire Finnish people.” In his opinion, the reason for the good preservation of the epic runes in Karelia was that “famous Karelian singers still firmly remembered that their ancestors were in the hitherto wild land from Eastern Finland during the Northern War; their language still keeps traces of contact with the eastern Finns and the Swedes. ” The scientist also cites two points of view on the Kalevala. Does it represent a folk poem created by E. Lönnrot in the spirit of folk singers, or is it an artificial formation made by Lönnrot from various fragments. Further V.A. Gordlevsky notes that, of course, modern scholars reject the form of the Kalevala as a folk poem, because in this form it has never been sung by the people, although, the author continues, it could have resulted in such a form. In the end, Gordlevsky emphasizes that "at its core, the Kalevala is a folk work captured by a democratic spirit." This article, rich in correct information and fruitful ideas, gave a powerful impetus to the study of Kalevala in Russia.

This topic was continued in 1915 by the translator of Kalevala into Russian L. Belsky, but, unlike Gordlevsky, it is more categorical. Thus, in the preface to his translation, he wrote that the works of scientists "destroyed the view of her as an integral work of the Finnish people, that" Kalevala "is a series of separate epics and other kinds of folk poetry artificially linked into E. Lönnrot's epic. songs and conspiracies. Inspired by the desire to give something like Homer's epic, E. Lönnrot connected organically unconnected.

At the same time, the teachings of K. Kron and his school are spreading in Finland. In his opinion, such a work as “Kalevala”, “the most valuable of what was created in Finnish, could not have originated among the poor and illiterate Karelian people”. However, the long-term efforts of Crohn and his school were in vain. In Western Finland, no runes related to the Kalevala theme were found, and no heroic and epic songs were found, although the search began in the 16th century. Basically discovered Catholic legends and semi-religious spells. Despite this, K. Kron created a theory based on a whole chain of assumptions, according to which the Kalevala runes originated in western Finland in the late Middle Ages and were “supposedly” sung in the houses of the then Finnish aristocracy and “supposedly” were spread by professional roving singers. In 1918, Kron replaced this theory with a new one.

According to the new theory, he pushes the time of the birth of the Kalevala runes about half a millennium ago, that is, from the late Middle Ages to the end of the Scandinavian Viking period. In the Kalevala Guide to Epic Songs, he gave such a “psychological” explanation: “During the struggle for our independence, the era when the Finns, for their part, independently marched off the coast of Sweden, appeared to me.” Thus, Professor Kron invented a whole heroic era of Finnish sea thieves, in order to draw on to this era the miracle of the origin of the Kalevala runes. But, in spite of the apparent fantasticality, the theory of Crohn influenced Finnish scientists studying the Kalevala.

In Soviet Russia, interest in the Kalevala was manifested in an article published in Volume 5 of the Literary Encyclopedia (1931), Professor D. Bubrin pointed out the duality of the Kalevala. On the one hand, this is a folk epic, since it was based on folk songs, but at the same time they underwent processing and their connection was very conditional. Also interesting are the judgments of E.G. Kagarov about “Kalevala”, expressed by him in the preface to the publication of “Kalevala”. He remarked: "The Kalevala was compiled in the middle of the XIX century, and the unity of the poem is explained to a certain extent by the personal poetic intent of the compiler." In E. Lönnrot, he saw only a poet-editor, who, choosing a series of cycles and episodes and giving the epic a beginning and a denouement, turned it into a harmonious and unified whole. But at the same time neither Bubrin nor Kagarov used primary material in their studies, i.e. folk, lyric and epic songs and spells.

In 1949, the centenary of the “complete Kalevala” (final version 1849) was celebrated in Petrozavodsk. V.Ya. Propp with the report "Kalevala in the light of folklore." It presented new positions on Karelian issues, i.e. "Runes" were declared common property of western and eastern Finns.

But the report rejected O.V. Kuusinen, the former programmer and keynote speaker at the session. His report and the general theme of the jubilee were based on three theses: 1) “Kalevala” is not a book by E. Lönnrot, but a collection of folk songs edited by him; 2) songs of predominantly Karelian origin, rather than West Finnish; 3) the Kalevala runes did not arise in the aristocratic environment of the Vikings, but among ordinary people in the period preceding the Middle Ages. Thus, Kalevala is a great Karelian phenomenon, not Finnish culture. Therefore, the bold ideas of V.Ya. Propp in the Soviet Union did not come in time. In his book “Folklore and reality”, he writes that it is impossible to identify “Kalevala” and the folk epos. Since E. Lönnrot did not follow the folk tradition, but broke it. He violated the folklore laws and subordinated the epos to literary norms and tastes of his time. With this, he created Kalevala widespread popularity.

The two-volume V.Ya. is very informative. Evseev "Historical foundations of the Karelian-Finnish epos", published in the late 50s. Twentieth century. Where, from the point of view of historical materialism, the epic is disassembled line by line and compared with the body of the epic Karelian-Finnish songs. On the basis of this approach, it was recognized that the events inherent in the stage of decomposition of the primitive communal system are reflected in Kalevala and, accordingly, the question of its historicity has been resolved positively.

Repeatedly, E. Narn returns to Kalevala in his research. He sees the main difference between Kalevala and popular poetry in the fact that as a result of a certain revision of the storytelling options, a certain system of “assembling” the best places, the unification of names, “a new aesthetic integrity with a new meaningful level has emerged.”

In the 80-90-ies. XX century most of his research E. Karhu<#"center">Chapter 2. The history of the creation of "Kalevala"

2.1 Historical conditions of the occurrence of "Kalevala" and problems of authorship

An important component of our research will be the establishment of historical conditions that influenced the creation of the source of interest to us. At the beginning of the XIX century, and especially in the 20s. in the culture of Europe begins the heyday of the direction romanticism . This situation can be regarded as a response to such grandiose events as the Great French bourgeois revolution, the campaigns of Napoleon, who changed life in many European countries and redrew their boundaries. It was a time when the age-old foundations, forms of human relationships, ways of life broke. A major role was also played by the industrial revolution, which on the one hand led to economic growth, trade, an increase in the number of urban dwellers, and on the other, aggravated the already difficult social situation: becoming a source of the ruin of the peasants in the villages, and as a result of hunger, growth, crime, pauperization. All of this meant that the Enlightenment, with its faith in the human mind and universal progress, was untenable in its predictions. Therefore, a new cultural era of romanticism begins. For which are characteristic: disappointments in progress, hopes for improving life and at the same time a feeling of confusion in a new hostile world. All this gave rise to a flight from reality to some fabulous and exotic countries and gave where people tried to find the ideal of life.

Against this background, one can trace the increased interest in the historical past of nations. This contributed to the theory of G.-V. Hegel and Herder. Under their influence the formation of national ideologies took place. Therefore, the study of folk traditions, life and work has become so relevant. With the help of folklore, followers romanticism wanted to find one golden age , in which, in their opinion, their peoples lived in the past. And the society was then built on harmonious beginnings, and universal well-being reigned everywhere.

An image appears national poet who feels the charm and power of wild nature, natural feelings and, accordingly, folk legends and myths. Therefore, in Europe, many enthusiasts direct their forces to search and record various genres of folklore (myths, songs, legends, fairy tales, riddles, proverbs). A classic example here is the activity of the Brothers Grimm. The results of this work were mass publications throughout Europe of collections of songs, fairy tales, fictionalized stories from people's lives . Also such an increased interest in fairy tales, songs, proverbs can be explained by the fact that they have ceased to be considered something low, rough, simple and peculiar only to the common people. And they began to be perceived as a reflection national spirit as a manifestation genius of the people , with their help, it was possible to know the universal or even divine basis.

Later, when romanticism as a direction survives its first crisis, the attitude to folklore changes, a serious scientific approach will appear. Now it is perceived as a possible historical source. In many countries, national schools will be created to study these specific sources. Numerous theories, disputes and discussions on the topic of authorship and the origin of epics, mythical cycles continued even after the change of cultural direction.

All these cultural trends have not bypassed Finland, where they were fascinated by the entire educated part of society. It was in this setting that the author studied. Kalevala Elias Lönnrot Next, we consider in detail his biography, in order to understand how the personality of the author could influence the formation of the epic.

E. Lönnrot was born in 1802 in the south-west of Finland, in the town of Sammatti, in the family of a tailor. He was the fourth child among his seven brothers and sisters. Father’s craft and a small plot could not feed a large family, and Elias grew up in need and poverty. One of his first childhood memories was hunger. He went to school rather late at the age of twelve, to some extent this was filled up by the fact that Elias learned to read quite early, and he could always be seen with a book. At school, where instruction was conducted in Swedish, he studied for four years, first in Tammisaari, then in Turku and Porvoo. After that, he was forced to suspend training and began to help his father in his craft. Together they walked through the villages, working with customers at home. In addition, Lönnrot was engaged in self-education, worked as a roving singer and performer of religious chants, and was also a student of a chemist in Hämmyenlin. In this work he was helped by the fact that he learned Latin at school, reading the Latin dictionary. Phenomenal memory, perseverance and a desire to study further helped him to prepare for entering the University of Turku on his own. And as his biographers have established, that neither before him, nor many decades after him has anyone else from these places had a chance to study at a university. Here Lönnrot first studied philology, and his thesis was devoted to Finnish mythology and was called About the god of the ancient Finns Väinamöinen . In 1827 it was issued as a brochure. Then Lönnrot decided to continue his education and get a doctor’s degree. But in 1828 a fire broke out in the city, and the building of the university burned down, the training was suspended for several years, and E. Lönnrot had to become a home teacher in Vesilath.

After graduating from university, in 1833, he received the position of the district doctor in the small town of Kajaani, where the next twenty years of his life passed. Kayani was a city only in name, in fact it was a rather miserable place, with four hundred inhabitants, cut off from civilization. The population often went hungry, and now and then terrible epidemics broke out, which claimed many lives. In 1832-1833, there was a poor harvest, a terrible famine broke out, and Lönnrot, as the only physician in a vast district, had enough worries beyond measure. In the letters, he wrote that hundreds and thousands of sick, extremely emaciated people, also scattered over a space of hundreds of miles, expected help from him, and he was alone. Along with the practice of medicine Lonnrot acted as a popular educator. In the newspapers, he printed articles for the purpose of gathering for the hungry, published an urgently reprinted in Finnish language brochure “Councils in the event of a poor harvest” (1834), wrote and published a medical reference book for peasants in 1839, and compiled Legal guide for general education . Also his great merit was writing a popular book. Memories of people's lives at all times co-author in Finnish Stories and Stories of Russia . With his own money, he issued a magazine. Mehilyainen . For great services to science in 1876, he was elected an honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Used to characterize the author's identity Kalevala source Travels of Elias Lönnrot: Travel Notes, Diaries, Letters. 1828-1842. , allowed me to get an idea of the scientist’s style of work, areas of his scientific interests, and with what techniques Kalevala was created.

2.2 Circumstances of the creation of “Kalevala” as a historical source

Next, we would like to trace the history of the birth of folklore studies in Finland. This will help us to understand how E. Lennrot's scientific interests were formed and what materials he could rely on in his work. It is worth noting that interest in folklore has always been present in Finland. The founder here can be considered Bishop Mikoela Agricole, who, in the preface to his translation of the “Psalms of David” in Finnish, draws the attention of priests to the fact that among the Finnish pagan gods are Väinämainen, Ilmarinen, Kalevala, Ahti, Tapio, and among the Karelian gods - Khiyesi. By this, the bishop showed practical interest in the names of the heroes of the Karelian-Finnish epic. Since he was actively engaged in the struggle against the pagan views that still remained with him among the Karelians and Finns. In 1630, the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf issued a memorial, according to which he commanded to record folk legends, legends, stories, songs, telling about past times. The king hoped to find in them a confirmation of the original rights of the Swedish throne to own vast territories in northern Europe. Although this goal was not achieved, the beginning of the universal gathering of folk poetry was made. With approval romanticism in culture as the main direction led to an increase in interest in the manifestations of folklore.

The first collector, propagandist and publisher of folklore in Finland was the professor of rhetoric at the University of Turku, H.G.Portan (1739-1804), who published his dissertation “On Finnish Poetry” in 1778 in Latin. In it he put folk songs above the “artificial” poetry of the authors of that time.

No less famous is Christfried Hanander (1741-1790). In the works The Dictionary of the Modern Finnish Language (1787) and Finnish Mythology (1789) he quoted many examples of folk poetry. The Finnish Mythology, which has about 2,000 lines of Karelian-Finnish runes, is still the reference book for researchers of the poetry of the Kalevalsky metric. The commentary and interpretations of the content of the song fragments are extremely valuable.

The emergence of studies of folk poetry by Professor D. Yuslenius, H.G. Porta et al. An important role in the preparation of Kalevala was played by collections of texts by folklorist and enlightener KA Gottlund (1796-1875), who first expressed the idea of creating a single folklore arch. He believed that if you collect all the ancient songs, then one could form some kind of integrity, similar to the works of Homer, Ossian or "Song of the Nibelungs."

The immediate predecessor of E. Lönnrot was S. Topelius (the elder), the father of a famous Finnish writer who published in 1829-1831. five notebooks of folk epic songs collected from Karelian peddlers who brought goods from White Sea Karelia to Finland (85 epic runes and spells, a total of 4,200 verses). It was he who indicated E.Lönnrot and other enthusiastic gatherers to the White Sea (Arkhangelsk) Karelia, where "the voice of Väinämöinen still sounds, the chanter and Sampo ring". In the 19th century, individual Finnish folk songs are published in Sweden, England, Germany, and Italy. In 1819, the German lawyer Kh.R. von Schröter translated into German and published in Sweden, in the city of Uppsala, a collection of songs called Finnish Runes, which featured spell poetry, as well as some epic and lyrical songs. In the XIX century. epic, enchanting, wedding ritual, lyrical songs were recorded by A.A. Borenius, A.E. Alquist, J.-F.Kayan, MAKastren, H.M.Reinholm and others - altogether about 170 thousand lines of folk poetry were collected.

At this time, the idea of the possibility of creating a single epos from scattered folk songs Finn and Karel is born by one person or a group of scientists. This was based on the theory of the German scientist FA Wolf, according to which Homer's poems are the result of a later work by the compiler or compilers of songs that previously existed in oral tradition. In Finland, this theory was supported by such scientists as H.G. Portan and K.A. Gotlund As early as the end of the 18th century, H. G. Porta suggested that all folk songs come from a single source, that they agree with each other on the main content and main subjects. And by comparing the options with each other, you can return them to a more consistent and appropriate form. He also came to the conclusion that Finnish folk songs can be published in the same way as the "Songs of Ossian" by the Scottish poet D. Macpherson (1736-1796). Portan did not know that MacPherson had published his own poems under the guise of the songs of the ancient blind singer Ossian.

At the beginning of the XIX century, this idea of Porta acquired the form of a social order expressing the needs of the Finnish society. Well-known linguist, folklorist, poet K.A. Gottlund, as a student, in 1817 wrote about the need for the development of "national literature." He was sure that if people wanted to form an orderly integrity out of folk songs, be it an epic, a drama or something else, then a new Homer, Ossian or "A Song of the Nibelungs" would be born.

One of the reasons for the increased interest in folklore, in our opinion, is the change in the legal status and position of Finland on the world map. In 1809, the last war between Russia and Sweden over the northern territories, including Finland, Karelia and the Baltic States, ended. And this struggle lasted with varying success for almost a thousand years, starting with the Varangian and Viking campaigns. There was an era (HUI-HUP centuries), when Sweden was considered a great European power Finland for six centuries belonged to Sweden. The Russian emperor Alexander I, having conquered Finland and wanting to diminish the Swedish influence in it, granted the Finns autonomous self-government. And in March 1808 the people of Finland were solemnly proclaimed a nation with their own laws, an autonomous form of statehood.

But at the beginning of the 19th century, the Finnish nation as such did not exist yet, it had yet to be created, and the all-round development of the national culture played a huge role in this along with the socio-political and economic development. The legacy of Finland’s centuries-old domination of Finland went to the administration, the system of school and university education, the press and all public cultural life. The official language remained Swedish, although it was only available to one tenth of the inhabitants. These included the upper classes, educated circles, still few urban populations.

Ethnically, Finnish linguistically and culturally was the peasantry, the main population of the region. But in terms of language, it remained powerless, in the official life of his language had no access. This was one of the reasons for the delay in the natural evolutionary process of the folding of the Finnish nation. The threat of Swedish assimilation also remained relevant, since there were less than a million Finns. All this led to the search for national identity, cultural traditions and, as a result, national self-affirmation.

The combination of these prerequisites for E. Lönnrot formed an interest in collecting folklore, and taking advantage of a forced break in training, he relied on the advice of E. Topelius (the elder) in 1828 on his first of 11 trips to Finland in Karelia and Sava province to record the remaining runes. For four months, Lennroth collected material on five notebooks of the Kantele collection (four of them were published in 1828–1831). He wrote down more than 2,000 lines from the ringleader from the parish of Kesalahti Juhani Kainulainen. Already in this collection Lennroth used the method rejected by Russian folklore studies: he connected lines of different songs. I took something from the collections of K. Gottlund and S. Topelius. Already in this edition, Väinämainen, Ilmarinen, Lemminkäinen, Pellervoinen, Loukhi, Tapio, Mielikki and others acted as characters.

Only in 1832, during the third journey, Lennrot managed to reach the villages of Russian Karelia. In the village of Akonlahti, he met Soav Trohkimaynen and recorded several epic songs. The heroes of which were Lemminkäinen and Kavkomieli, Väinämöinen, who makes Sampo and Kantele.

The fourth expedition of Lennrot became very successful in 1833, when he visited the northern Karelian villages of Voinitsa, Voknavolok, Chen, Kiviyarvi, Akonlahti. An important role in the history of the creation of Lönnrot "Kalevala" was played by the meeting with the band members Ontrei Malinen and Voassila Kieleväinen. Based on the recorded material, a collection was prepared Wedding songs . The material collected during this trip made it possible to create a multi-hero poem. Prior to that, Lönnrot worked on poems about one hero (Lemminkäinen, Väinämöinen).

New poem Lennroth called the "Collection of songs about Vainamainen." In science, it received the name "First Kalevala". However, it was already printed in the twentieth century, in 1928. The fact is that Lennroth himself delayed its publication, as he soon set off on the fifth journey, which gave him the greatest number of songs. For the eighteen days of April 1834, he recorded 13,200 lines. He received the main song material from Archippa Perttunen, Martiski Karjalainen, Jurkka Kettunen, Simana Miihkalinen, Varahvontty Sirkeinen and the narrator Matro. One famous A. Perttunen sang to him 4124 lines.

"First Kalevala" contained sixteen chapters-chants. Already in this poem was developed the main plot and conflict. However, as V. Kaukonen wrote, Lennrot has not yet found an answer to the question of where and when his heroes lived. In the "First Kalevala" Pohjola was already there, but there was no Kalevala. Sampo in this poem was called Sampo. It looked like some kind of wonderful barn with never-drying grain. The heroes brought him to the cape of a misty bay and left him on the field.

Returning from the fifth trip to Kajaani, Lennroth began to rethink the epic story. According to the testimony of the same Kaukonen, Lennrot now makes additions and changes to the text of “First Kalevala” in all its chapters and so many that one can hardly find 5-10 lines in a row taken from a particular folk song and preserved in its original form. And most importantly: he came up with a plot. By making Aino (an image mostly fictional by Lennrot) sister of Youkahainen, Lennrot urges Youkahainen to avenge old man Väinämöinen not only for losing the competition in singing, but also because Väinämainen is guilty of his sister’s death.

Any episode of "Kalevala" compared to popular sources is different from them. To explain how this or that episode turned out to be under Lennrot's hand, it is necessary to write whole studies. Taking from the runes sometimes only a few lines, Lennroth unwrapped them and put them in the general plot. The singers knew very little about what Sampo is, how it is done, and they sang about three to ten lines about it, not more. Lennrot has a whole story on Sampo on many pages. Having, in fact, only one shepherd’s song where Kalevala is mentioned, Lönnrot composed the country where Väinämöinen, Lemminkäinen and Ilmarinen live.

The first version of Kalevala, published in 1835, consisted of 32 runes, with a total number of lines exceeding 12,000 thousand and had the following name Kalevala or ancient Karelian songs about ancient times of the Finnish people . Then E. Lönnrot continued the search for folk songs and work on the poem. This work continued for another fourteen years. In the years 1840-1841, based on material collected during several previous trips, a three-volume poetry collection was published Canteletar who is also called the younger sister Kalevala . It contained separately recorded female folklore i.e. wedding, ceremonial songs, laments, spells, as well as a variety of runic songs recorded from more than a hundred storytellers.

When working on an extended version of the epic, the author achieves tremendous creative freedom. From 1835 to 1844 he makes six more expeditions, visiting, besides Karelia, the region of Northern Dvina and Arkhangelsk, as well as Kargopol, Vytergu, Petersburg province, Estonia. By 1847, E.Lonnrot already had about 130 thousand lines of runes records. New material has accumulated so much that he said: "I could create several Kaleval and none of them would be like the other."

E.Lonroth's titanic work was completed in 1849, when the “complete” Kalevala was published, consisting of 50 runes or 22,758 verses. This “canonical version” of the Kalevala is now known all over the world. Her appearance was enthusiastically greeted by the public, causing a real boom among collectors and fans of folk poetry. Dozens of folk song collectors headed to Karelia, and later to Ingria. Some wanted to make sure that the plots, themes, motifs, characters of Kalevala are not fictionalized by E. Lönnrot. Others went in search of new runes that were not found by E. Lönnrot.